In early 2020, COVID-19 rates were soaring. Masks, cleaning supplies, and clear information were in short supply. This was especially true for schools across the country. Teachers, parents, and students were unsure about what was going to happen next. On Thursday, April 1, 2020 (in-person) school was still in session in the Genesee Intermediate School District (GISD) and the students and staff of the 21st CCLC Brides to Success afterschool programs were looking forward to a 4-day weekend. On Friday, April 2, Governor Whitmer released executive order 2020-35, immediately suspending school for the remainder of the school year and drastically changing how delivery of school and afterschool services would be provided (e.g., shifting from in-person to remote interactions with children and youth).

This was the second year QTurn partnered with GISD’s Bridges to Success programs, and we quickly realized two things. First, our original continuous quality improvement (CQI) cycle (with a heavy focus on Socio-Emotional Learning) was, in spirit, more relevant than ever but, in implementation, completely inappropriate. Second, the setting-based tools (such as the Youth and School-Age PQA) available to evaluators in the OST field in April of 2020 could not provide valid program quality data and could not demonstrate how afterschool programs, like Bridges to Success, were pivoting to meet the needs of children.

During this pivot point, we discovered the four “rules” for designing and implementing a compassionate evaluation. It was clear that it felt unethical (to us and to the Bridges to success leadership) to ask staff to partake in an external evaluation processes ill-fit for the transitional physical setting or within the greater context of learning during a global pandemic. Our partners didn’t need the added pressure of an external observation while they were still figuring out what it meant to offer virtual and non-virtual programming to students and families.

By the time schools were closed in Michigan, QTurn was in the midst of developing a self-assessment tool for evaluating program quality during the COVID pandemic, which would eventually become the Guidance for OST Learning at a Distance (GOLD). The development of the GOLD, funded by the Michigan Afterschool Association (MAA) and the Michigan Department of Education (MDE), was the culmination of interviews, workshops and reviews with over 25 youth development and OST experts from the State of Michigan. Because the GOLD materials were not released for another month to the public, the QTurn team and Bridges to Success leadership decided to use the 27 best practices described in the GOLD as a framework for coding a series of interviews in order to tell the story of Bridges to Success’ response to the pandemic.

Over the course of two weeks, the QTurn team interviewed 15 afterschool staff, from 9 GISD afterschool sites, and 1 administrator from the GISD office. Each interview was structured around the following five questions:

- What is the experience of transitioning from in-person to distance programming?

- What are you hearing from students and families?

- What are the barriers to students’ virtual learning?

- Where are you experiencing success?

- Where could you be successful with more support?

Some calls were quick, lasting only 35 minutes. Some were over an hour. We asked questions, and we listened, asked follow up questions, and listened more. Every conversation was an intense opportunity for direct staff, program administrators, and team leads to tell someone outside of their world what was going on. We heard many sentiments filled with hope and gratitude, confusion and uncertainty of their impact, moments of fear and sadness, and overwhelming concern for the students and families in their programs.

Although each of the afterschool sites used their own approach to providing services intended to facilitate learning at a distance, with no systematic coordination across sites, five key themes emerged from our analysis of the interview responses:

- Staff were unsure about how to define some aspects of program quality and/or professional practice within the context of learning at a distance; particularly, how to most effectively monitor children’s (a) socio-emotional well-being, (b) academic effort and progress, and (c) attendance.

- GISD Bridges to Success leadership style and organizational culture were important sources of support for staff experiencing programmatic uncertainty and professional disequilibrium.

- Learning at a distance both exacerbates and clarifies inequities. GISD responded by providing a diverse set of programming options, such as: (a) virtual communication and supports, (b) non-virtual communication and supports, and (c) supports for adults supporting younger children.

- GISD continued to deliver a whole-child curriculum that provided supports for safety, fun, academic work, and socio-emotional skill building.

- Increased flexibility of staff schedules was necessary to meet student and family needs, even though it often increased the length of staff workdays.

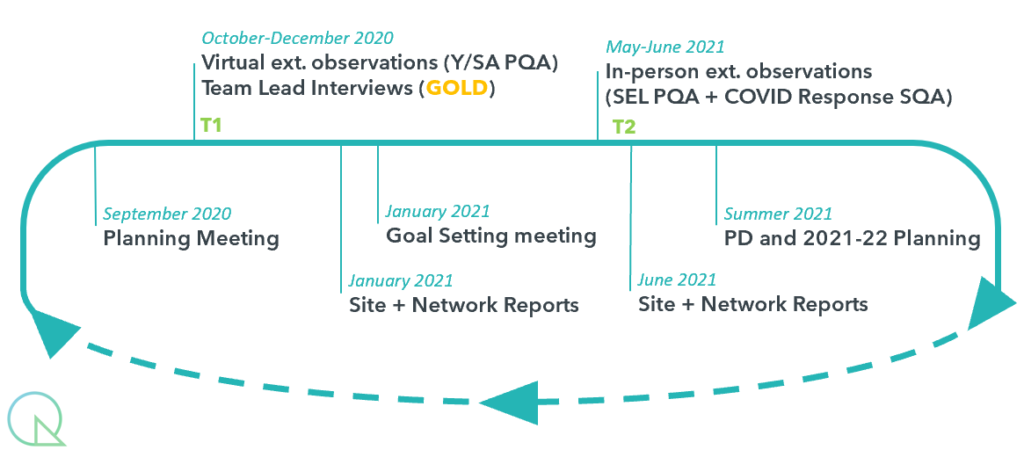

When we started the 2020-2021 school year, we realized again that the setting-based assessments required by the Michigan Department of Education were going to once again offer incomplete data on the impact of programming being offered by Bridges to Success. The afterschool model was no longer face-to-face general enrichment programming. Bridges to Success was still responding to families in crisis, so their approach was a casework model focused on socio-emotional and academic support. Knowing this, we conducted external (virtual) program evaluations, using the MDE recommended PQA items plus two scales from the SEL PQA (emotion management and empathy), But, the PQA data alone felt incomplete. To supplement, we again interviewed site leads and coded the transcripts to the GOLD. By interviewing site leads based on general questions, and letting them talk, we were able to learn about not only their experiences but also what they were most concerned with and focused on. The GOLD demonstrated what the PQA alone could not: that lots of SEL programming was being done but mostly one-on-one with children and families, outside of their regularly-scheduled virtual programming

In early spring, 2021, QTurn and Bridges to Success staff came back together to decide how we could work together for the rest of the year. Schools were opening again, and in-person afterschool programming would be offered again. We decided that would do external observations using the SEL PQA and use a custom distance-learning external assessment tool that was designed specifically for GISD.

By adding the GOLD into our CQI plan, we were able to really define the quality and breadth of services. No two sites were operating the exact same way – but every site was working with their school to meet the needs of children. Utilization of setting-based assessment tools not designed for virtual learning (or non-virtual distanced learning) was only scratching the surface of what programs like Bridges to Success accomplished on 2020-21. And by working with our partners and by centering compassion, our evaluation not only articulated, but honored the heroic effort and continuous dedication of the Bridges to Success program to their communities during a difficult year.